The journey to well-being economies

Today’s economic system was created in the aftermath of global war. It was meant to prevent another war. It’s purpose was never explicitly about generating well-being.

Take this journey through time to see where today’s economic model came from and where we have to go to create and normalize well-being economies.

The Great Depression

During the 1930s, an economic downturn devastated the industrialized world. After the panic of a stock market crash in 1929, millions of investments were wiped out, consumer spending dropped, workers were laid off as banks and companies failed, and families suffered. Canada was one of the most severely affected countries because of its dependence on raw material and farm exports, along with a massive drought in the Prairies. By 1933, 30 per cent of the labour force was unemployed, one-fifth of Canadians depended on government aid, and the total national income fell to less than half of the 1929 level.

The New Deal

After the Great Depression, Canada’s leaders ushered in a new wave of large-scale public spending, including welfare and minimum wage. It was modelled after President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal in the U.S. With limited success in rebooting the economy, it wouldn’t be until 1939 and the outbreak of the Second World War that Canada would see its economy return to pre-Depression levels.

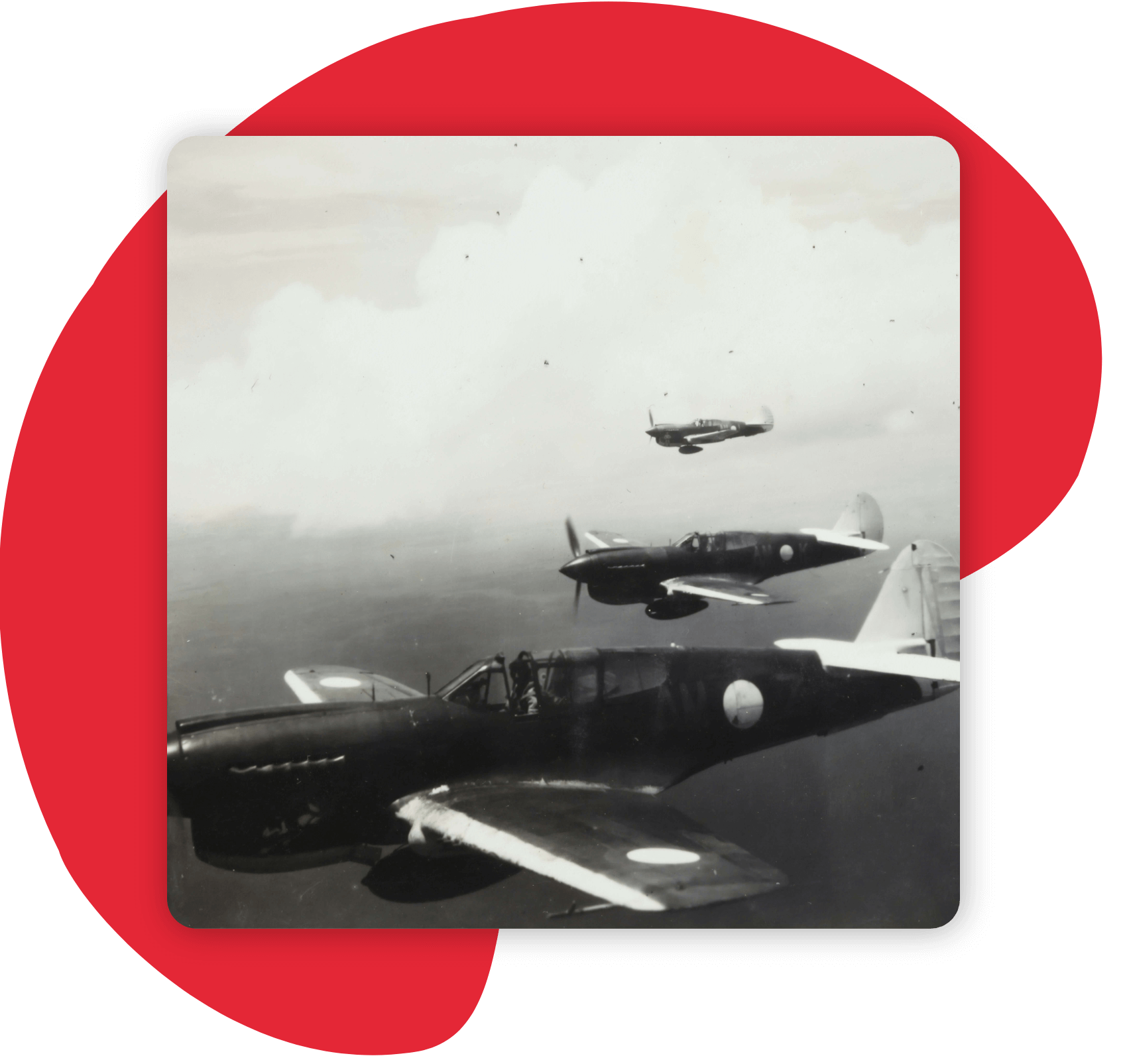

Second World War

During the war, Canada manufactured nearly $10 billion in war materials for allied countries. Income from wheat production increased to over $80 million (1940s dollars). Out of its population of just over 11 million, roughly three million people were employed in the war effort. More women and teenagers entered the workforce. Despite embracing a form of economic communism in war production, it was a booming time for the country.

Bretton Woods Conference

Nobody wanted another war, so 730 representatives (all men and mostly white) from 44 allied nations came together in Bretton Woods, U.S., to create a new set of multilateral economic cooperation rules. Establishing an international monetary and financial system would help foster co-operation and growth, and avoid another war, they believed. Out of Bretton Woods came the International Monetary Fund and World Bank and a currency exchange regime.

GDP is born

Gross national product was developed in 1937 by economist Simon Kuznets as a way to calculate economic production. His theory was that it would rise in the good times and fall in the bad. After Bretton Woods, gross domestic product became the standard tool for evaluating a country’s economy.

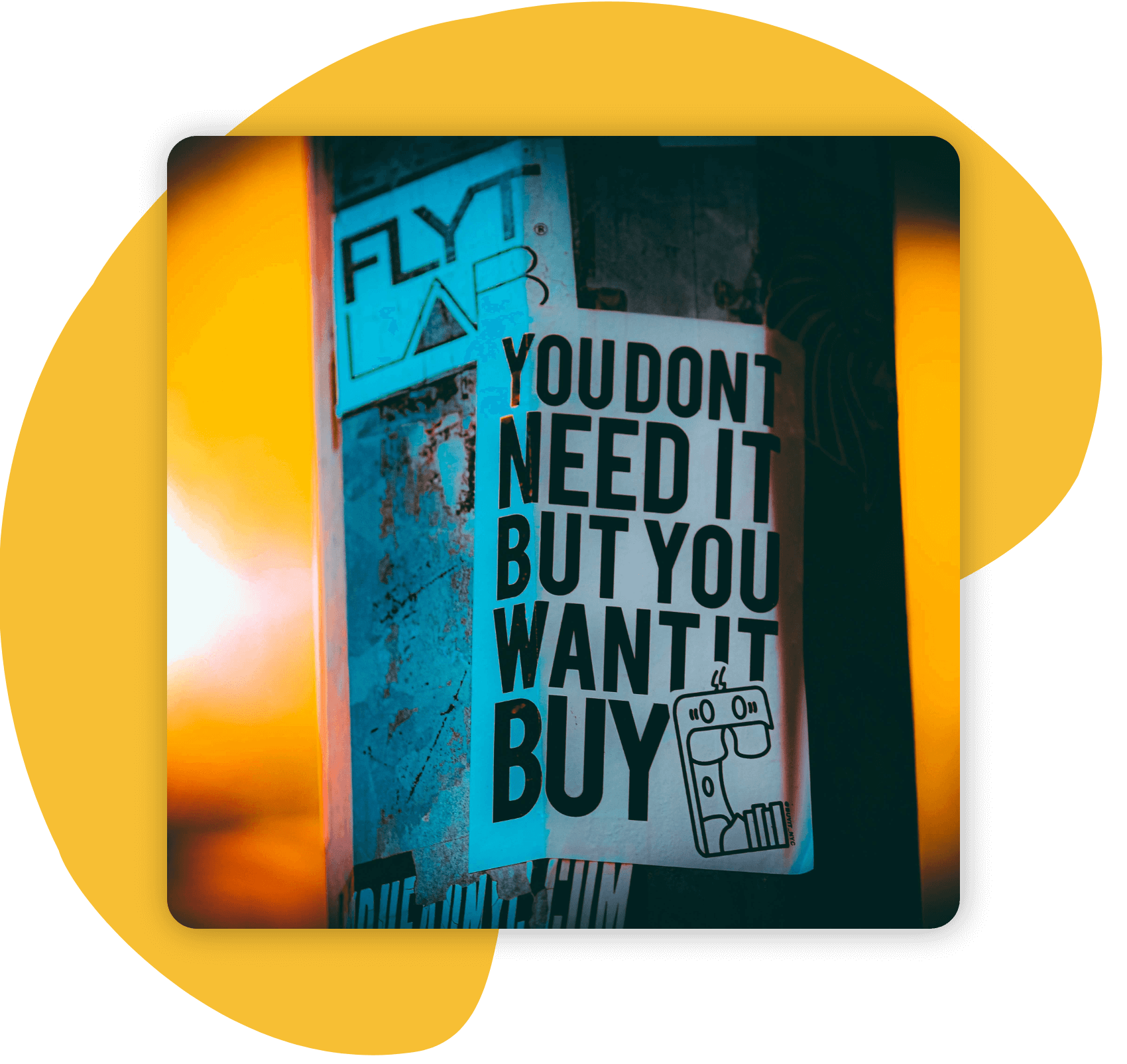

The birth of hyper-consumerism

All of that wartime production had to go somewhere. Consumers were suddenly hailed as patriots doing their national duty to help the country’s economy stay strong. Where once frugality was praised and products were made for their usefulness and longevity, profit and growth were the new kings. “Newer, better, more” became the mantra. Money became the most important value in society.

The linear economy

To meet the growing demand of consumers, the economy transformed into a linear one, converting natural resources into products that are consumed and ultimately thrown to waste at the end of their life cycle. It is based on a “take-make-consume-waste” approach to using resources, which doesn’t factor in their finite nature. It creates waste, degrades nature, ignores justice and fails to ensure equity. After years of aggressively pursuing this path, the world has come to a tipping point and will soon be unable to sustain itself.

The obsession with GDP

Gross domestic product is a monetary measure of the value of all final goods and services produced in a period. It is commonly used to determine the economic success of a country and to make international comparisons. GDP, however, says very little about a nation’s well-being. Things like happiness, work satisfaction, leisure time, community ties, health and the environment all fall outside its scope. What good is a strong economy if you’re working 16 hours in a job you hate and never get to see your family?

The rebirth of well-being economies

What would a new economic model look like? Indigenous Peoples the world over have been guided by the principles of well-being economies since time immemorial. These principles respect — even nurture — nature and help enhance the things we truly care about, like health, collective prosperity and well-being.

It is a reimagining of economic purpose that puts people and the planet at its heart. It’s already happening in countries like Scotland, New Zealand, Bhutan and Iceland, and WEAll Can was born to dream the possibilities and enable the transition here at home.

Where do we go from here?

Well-being economies may look different in different places. There is no “one size fits all” when it comes to creating them. However, well-being economies will share certain characteristics.

They must be designed with purpose (to grow well-being), regenerative, fair, redistributive, secure and collaborative.

It’s possible, but that’s not to say it will be easy. It will require strong will and determination at all levels of society. Governments will need to make the legal changes necessary to support the transition.

Businesses will need to shift their focus from profit to well-being. People will need to support those businesses that are taking the first steps. It’s up to all of us to make it happen.